ARTICLE AD BOX

This is a segment from The Breakdown newsletter. To read more editions, subscribe

“I do not fear computers. I fear the lack of them.”

— Isaac Asimov

When ATMs became commonplace in the 1990s, people naturally thought most bank tellers would soon be out of a job.

They weren’t.

The number of tellers per branch did in fact go down, from 23 to 13.

But, as Benjamin Todd notes, ATMs made bank tellers more productive (because they were freed up to do higher-value work) and bank branches more profitable.

So banks opened more branches — so many more that the total number of bank tellers actually rose.

That happy result held all the way until 2018, when online banking reduced the need for bank branches, which caused the total number of bank tellers to go down.

“While partial automation increased employment,” Todd concludes, “the more dramatic automation made possible by online banking did indeed reduce it.”

Could AI play out the same way?

A paper published by Stanford University last week seemingly confirmed people’s worst job-pocalypse fears — that we’re skipping straight to the endgame of full automation.

The paper documents falling employment among recent college graduates in the most AI-impacted fields, like software engineering, and suggests that this is a “canary in the coal mine” for the job market — an early sign that AI is coming for all of our jobs.

The same exact data can, however, be used to reach the exact opposite conclusion.

Noah Smith looks at the paper’s findings and wonders why employment losses would only be found among the youngest workers.

If AI is ready to replace humans, wouldn’t companies fire their most expensive humans first?

Joshua Gans says the fact that companies have hired even more experienced employees is significant: It suggests that AI is making more experienced workers more valuable.

“If a new technology comes along that augments the productivity of existing workers,” Gans explains, “then any business will want to hire workers with the necessary skills and experience and fewer workers who don’t have those skills.”

From that perspective, Stanford’s paper is good news for human employment, not bad.

Like Tony Stark and his JARVIS assistant, AI is so far proving to augment human workers rather than replace them — and if augmented workers are more productive, the first-order effect of AI should be to make employment go up, not down.

The real problem now, Gans concludes, is businesses that have stopped hiring entry-level workers “are going to run out of workers with experience.”

If so, we might soon stop fearing AIs, and start fearing the lack of them.

Let’s check the charts.

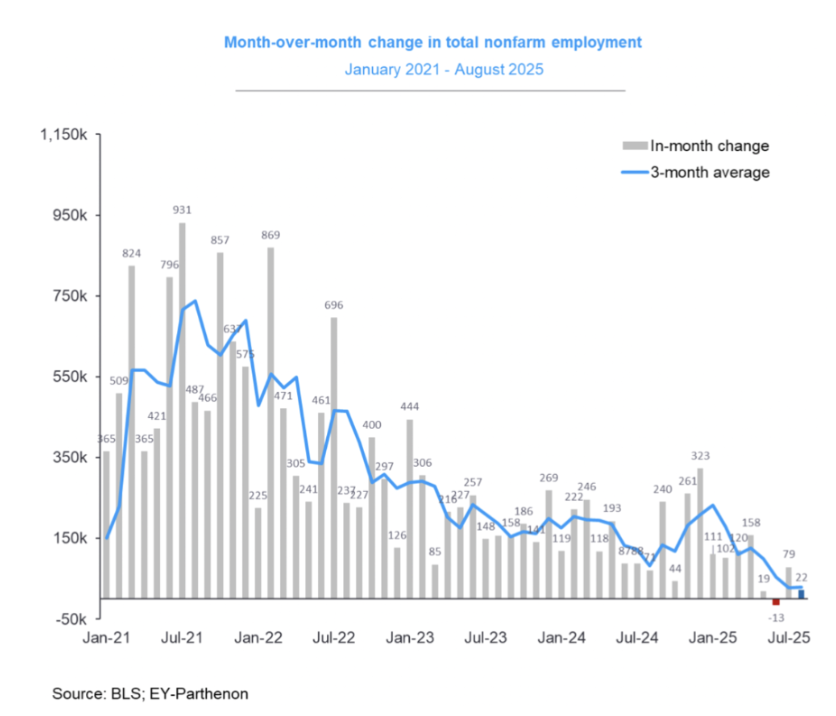

The trend is not our friend:

This morning’s mobs data showed that employment fell in June — according to the BLS’s model, which is not to be taken literally. Still, the trend is undeniably going in the wrong direction.

The AI effect:

From the aforementioned Stanford paper, its data on developer jobs by age group shows employment has fallen sharply for the youngest employees — but risen for the oldest. We can only hope that the same is true for newsletter writers.

More data:

Brian Armstrong shares that over 40% of the code at Coinbase is now generated by AI. But he also notes that the code “needs to be reviewed and understood” by humans. That would explain the Stanford paper’s finding that experienced developers are in higher demand — and maybe confirm Joshua Gans’ thesis that AI is augmenting workers, not replacing them.

Zooming out:

The unemployment rate for college graduates has ticked up, but remains within historic norms.

The ATM experience:

The best time to be a bank teller was the 18 years after ATMs arrived, because they made tellers more productive and bank branches more profitable. Online banking, however, was a replacement technology.

Look familiar?

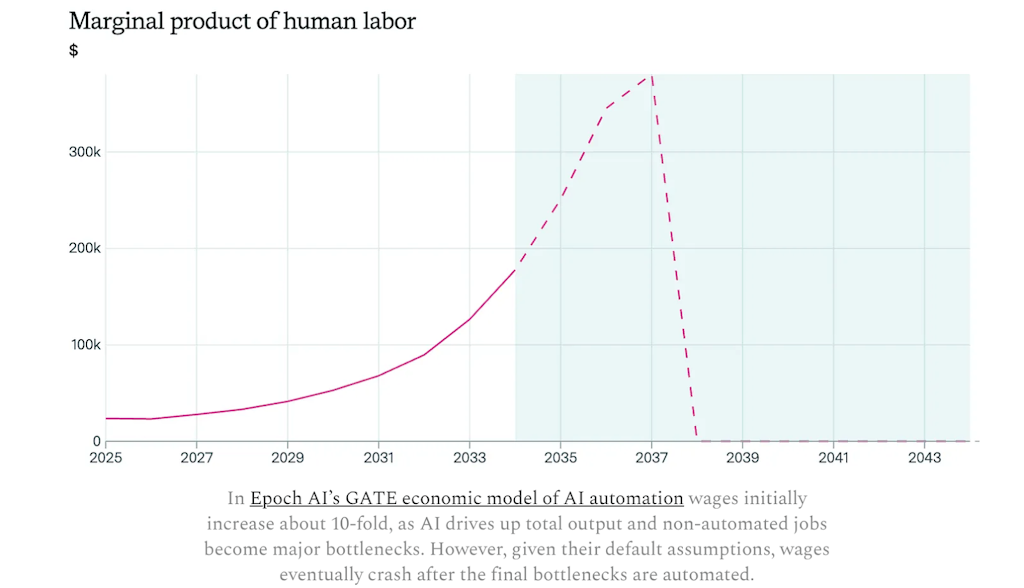

The researchers at Epoch AI predict artificial intelligence will be an augmenting technology in the first instance — causing wages to increase 10x in just over a decade — but then become a replacing technology, causing wages to crash. But Benjamin Todd notes that this assumes AI can do 100% of the jobs. “If instead humans remain necessary for just a small fraction of tasks, say 1%, then the same model shows that wages increase indefinitely.” In other words, we have somewhere between 12 and infinity years of rapidly growing wages to look forward to.

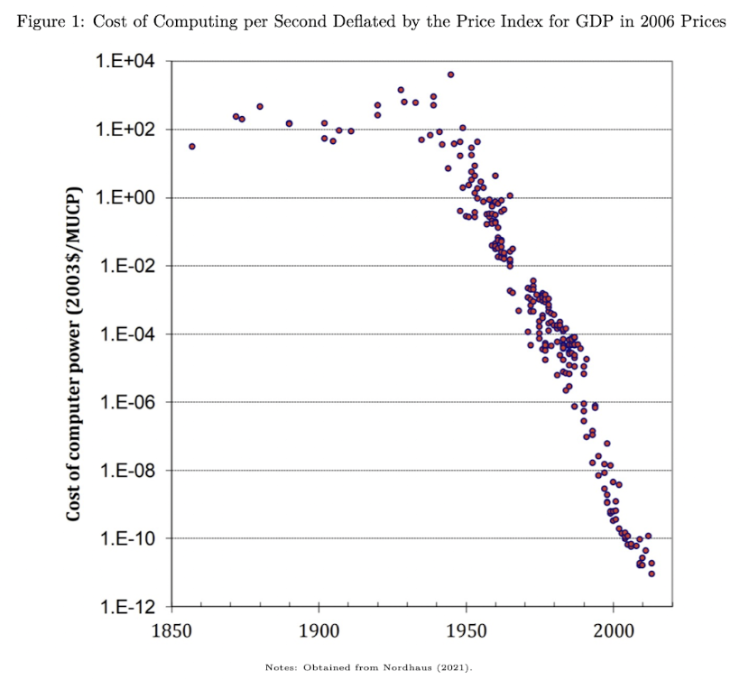

The falling cost of compute:

If AI is going to someday do 99% of the jobs, it’s going to demand a lot of power. This chart from a paper on the use of Gen AI in the workplace suggests we’ll figure out how to do it cheaply.

Not everything is AI:

Shares of Build-A-Bear are up 1,800% over the past five years — outperforming Nvidia by nearly 600 percentage points.

The long view (2):

A century of rising US employment through nonstop technological upheaval is reassuring proof that humans always find new things to do.

The example of bank branches and ATMs will still worry people, of course — even if AI is augmenting human workers now, it might replace them later.

But research by future-of-work economist David Deming suggests that employment always changes far slower than technology, so it’s unlikely to happen anytime soon.

Or ever.

“While AI helps with certain tasks of professional and managerial workers,” Deming concludes, “the demand for good ideas and cogent analysis of complex counterfactual thought experiments may be nearly unlimited.”

In other words, we might all be bank tellers making change today — and Tony Stark-like augmented humans doing superhero things tomorrow.

Let’s hope so.

Have a great weekend, augmented readers.

Get the news in your inbox. Explore Blockworks newsletters:

- The Breakdown: Decoding crypto and the markets. Daily.

- 0xResearch: Alpha in your inbox. Think like an analyst.

- Empire: Crypto news and analysis to start your day.

- Forward Guidance: The intersection of crypto, macro and policy.

- The Drop: Apps, games, memes and more.

- Lightspeed: All things Solana.

- Supply Shock: Bitcoin, bitcoin, bitcoin.

3 hours ago

207

3 hours ago

207

English (US) ·

English (US) ·